Somos en escrito The Latino Literary Online Magazine

Follow us on Twitter@Somosenescrito

|

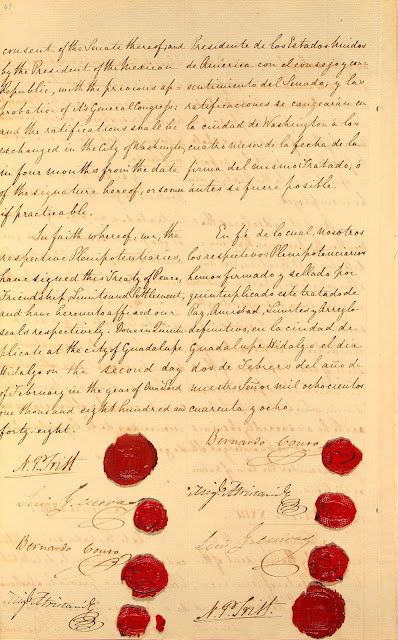

| Signature Page of Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, February 2, 1848 |

Editorial

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

What it may mean today

The 169th observance of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is today, Thursday, February 2. Ostensibly, the Treaty concluded hostilities between the U.S. government and Mexico, hostilities the U.S. had started.

I use the word, ostensibly, because for the intervening 169 years, a state of war has existed in terms of military incidents, punitive attacks by Texas Rangers in the 1910s, incursions by residents of one side or the other over the new boundary, often over a shallow trickle of water known as the Rio Grande, and a constant battle against the flow of drugs into the U.S.

And within the past few days, the new U.S. administration has pledged to build a wall, and somehow force Mexico to pay for it, as well as deport millions of undocumented Mexican migrants back to Mexico.

For generations, residents of Mexico and the U.S. along the border have moved back and forth for business and pleasure, the Tohono O’odham’s reservation has spanned both sides of the border along Arizona’s southern edge, and wildlife and plantlife proliferate in their way, paying no heed to boundaries: how would a border wall affect these realities?

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo would seem a dead letter given its age but in effect it is still very much alive. As an international document, it has been asserted hundreds of times over the years in property rights cases, land grant disputes, and the assertion of religious, treaty and other human rights by American Indian tribes.

I’ve not heard the Treaty cited by the Mexican authorities, principally the President of Mexico in his dealings with the U.S. President. Perhaps Mexico is loath to recall, let alone raise the Treaty as legal precedent in a formal suit; at least not yet.

Specifically, the Treaty contains Article 21, which clearly empowers one or both countries to seek arbitration before a third party of a conflict involving “the political and commercial relations of the two nations,” which may threaten the peace between them. Today, this would mean having recourse to the InterAmerican Commission on Human Rights (the Americas’ version of the UN Human Rights Council, formerly the UN Commission on Human Rights.)

Migration is considered a human right in the context of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the UN Charter, and by extension by the Inter-American system of human rights as well. The contention between the U.S. and Mexico could be brought before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, seeking resolution of the adverse relationship, perhaps resorting to the Inter-American Court of Human rights.

The point is that relations between the U.S. and Mexico are at an all-time low: The U.S. threatens somehow to deport the millions of undocumented migrants in the U.S., and the Mexican government has moved to protect its nationals living in the U.S. in a full-fledged pushback given the threat that the U.S. effort may result in gross violations of the human rights of migrants and affect U.S.-born persons of Mexican origin.

Between 1929 and 1936, it is estimated that as many as 2 million Mexican-origin men, women and children were deported, put on trains, buses, trucks and hauled off across the border. A large percentage was U.S.-born, that is, Mexican Americans. This government action was tantamount to the internment of Japanese families and individuals at the beginning of WWII.

A great deal of fear and anxiety have been aroused on both sides of the border, because the deportation of millions of people obviously would have an enormous impact on families which may be pulled apart, jobs and income wiped out, and the loss of migrants’ remittances (which amount to millions each year sent from the U.S. to Mexico). Would we force U.S. citizens, let’s say, the children of affected parents, to relocate in Mexico, even though their home is here?

According to the Pew Research Center, in 2008 Mexico accounted for 7 million of the 11.9 million “unauthorized immigrants” in the U.S., or 59%. Other regions of origin include Central America, 1.3 million (11%); South America, 775,000 (7%); the Caribbean, 500,000 (4%). South and East Asia, 1.3 million (11%), and the Middle East, 190,000, or less than 2%.

The political solution that has been argued and been the cause of heated debate over the past several years, and certainly as an issue in the recent electoral cycle is known as “immigration reform.” I underscore the word, political, because while it may be that through the legislative process, the many concerns and fears on both sides of the question may be resolved, the answer may lie outside of both countries’ powers, and find resolution by two nations resorting to the review and impartial regard of the Inter-American system for human rights.

Curiously, today’s inter-American and international processes designed to address contentions among nations find a thread leading back to a 169 year-old document that ended a shooting war and absorbed on the U.S. side of the new boundary, the first Mexican Americans.

−The Editor